The bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese ended up giving boys like Dale Wilson–of rural Minburn, Iowa–the chance to “try their wings” and enlist as cadets in the Army Air Force.

As a boy, Dale had carved planes out of wood for school exhibition, gotten into trouble for drawing airplanes on his school work, and even had a ride in a bi-plane. That plane had landed in a field near Dexter, where Wilsons lived. Dale, Danny, and Junior had hiked out to see it and they even asked the pilot for a ride. He agreed to take them if they could come up with three dollars. They ran back home, pooled their nickels and dimes, and hurried back to the plane. Imagine the thrill for young brothers of taking off in an open plane for the first time, having family and neighbors watching them fly right over their town, and flying low enough that when Junior tossed out his cap, it landed right in his mother’s garden.

The Army Air Force had urged men ages eighteen to twenty-six to become pilots, mechanics, navigators, and bombardiers. Dale’s dream was coming closer.

After Dale’s long train ride to the Santa Ana Army Air Base in June of 1942, he was more than 10,000 cadets from all over the United States. And what a hotbed of rumors–pilots washing out quickly, bitter disappointment, ending up in bombardier, navigator, or ground crew. Only a few of each class would get to be pilots.

He’d heard that you could be washed out even from fainting or getting dizzy from inoculations. “Well, if I’m lucky enough to get classified as pilot, I will certainly be on top of the world,” he wrote.

To earn a pilot’s wings, a cadet had to complete three stages of training—Primary, Basic, and Advanced. In Primary, they learned to take off and land a small plane, usually a Stearman biplane, along with turns, glides, and stalls. They were indeed to solo after just eight hours of training, with check-rides at 20, 40, and 60 hours. Dale could be washed out at any stage. Ground School included Weather, Aircraft and Engines, and Aircraft Identification.

In Basic Training, cadets logged seventy more hours of flying, including twenty at night and ten cross-countries, in a larger low-wing plane with an enclosed cockpit and several instruments. And nearly 100 hours of Ground School classes.

Advanced Training depended on whether he was assigned single- or multi-engine planes, which would also determine what he would end up flying in combat. If he didn’t wash out first.

Knowing that Dan and Junior were also thinking about trying for cadet when they were old enough, Dale described everything. Morse Code took a lot of practice, he said, but after awhile the “dits and dahs” went into the ears and out the pencil. In one letter home, he included the entire alphabet in Code so they could practice.

This early in the war, the military was trying to train pilots as quickly as they could and get them into combat.

Primary Training

Now was Dale’s big chance to actually become a pilot. One hundred fifty single-engine PT-13 Stearman bi-wing trainers awaited the 300 cadets at Hancock College of Aeronautics, Santa Maria, California. Dale climbed in a Stearman at his first chance and looked everything over. Bright blue fuselage with two open cockpits and yellow wings. Rudder pedals far apart. Throttle just right. Dale pronounced the plane “keen.”

In four or five hours he was to be able to take-off and land the plane, and then solo by eight hours. “You have to learn fast or they will wash you. This school has the reputation as being the toughest in the country; that is, they have had the greatest percentage of washouts. But this school has some of the best instructors and turn out some of the best pilots. The last Squadron that went through here had 88 make it out of 186 Cadets.”

“Well, I’m beginning to fly!” he wrote, signing “Cadet Dale R. Wilson.”

After cadets soloed, they were upperclassmen. Until then they were “gophers.” The upperclassmen got the showers first after athletics, while the gophers stood and waited. Gophers also did all the cleaning up of the barracks and admired the cadets who had passed their final sixty-hour check ride.

After he’d made five fair landings with his instructor, he was told to taxi over to the line. The instructor climbed out, asking, “You know what this means, don’t you?”

The instructor said that he wouldn’t let him solo if he wasn’t sure he could handle it.

Dale zigzagged down the field, looked around for other planes, and took off. The front of the plane seemed light without the instructor so he set the trim-tab back a little. He expected to be tense on the controls but was much calmer alone. His landing was the best he had ever made, according to the instructor. “Boy, it makes one feel keen and more confident.” He hoped to keep writing letters that did not contain the words “I have washed.” But by the end of that week, thirty cadets in his squadron had already washed out.

“I did it! I have soloed!” Dale wrote on August 22.

The night before he left Santa Maria, Dale waited in line over an hour to call home, anxious to let his folks know that he had passed. At first he couldn’t even hear his mother. There were eight or nine families on Wilsons’ party line. Many of them would “rubber” or listen in when they heard a ring for another family. Each receiver off the hook weakened the volume. “Central,” the operator, had to ask the others to please hang up, and they did.

Dale also talked to Danny, Junior, and his dad, saying they sounded as if they were right beside him. Dale imagined himself in the kitchen at home. He said it was the most he ever got out of $2.50 in his life.

Basic Training

At Gardner Field, California, cadets trained in the Vultee Valiant BT-13. Nicknamed the Vultee Vibrator, the low-wing monoplane looked like a real airplane, aluminum with enclosed cockpits. Like the Stearman, it was blue with yellow wings–easy to spot if lost. Dale thought it looked awfully big, and had a maze of instruments–25 or 30, radio, manifold pressure, carburetor air temperature–compared with the four in the primary trainers. And he’d need to remember flaps, propeller pitch, and mixture control. “When they take off, they have the propeller in low pitch and they really beller and whine.”

By gosh,” he wrote after his first ride in one, “it is exactly like they said, that it is just like stepping out of a Model T Ford into a big Buick.” They had 450 horsepower Pratt and Whitney engines and cruised about 150 miles an hour. The ride was so smooth and the landing at ninety miles an hour was nearly twice as fast as a primary trainer. “The ground comes up fast and goes by fast.”

Basic training included seventy hours of flying, twenty of night flying, and ten of cross-countries. Ground School included an hour of chemical warfare defense, six of aircraft identification, twenty of Morse Code, ten of radio communications, 38 of weather, and ten of navigation.

Dale could see everything sitting up front in the BT-13, and pronounced it keen. The instructor sat in the rear seat and talked to him through an interphone. The controls in the BT-13 were very sensitive. “To do a medium-bank turn, you use practically no aileron and about 1/4 inch of rudder. This is a rudder ship. After establishing your desired bank, you of course neutralize both rudder and stick. It sure surprised me how little a movement of the controls is needed.”

He soloed after just four hours and 25 minutes. “It was a thrill, all right.”

They also logged fifteen hours in a flight simulator called the Link Trainer–“You know–that funny little airplane that can’t fly (actually); the little airplane that a pilot can land 100 feet under the ground or below sea level and crawl out unscathed but sometimes bewildered. ha.”

Cadets were to choose whether they wanted to go on to pursuit (fighter) or bombardment (twin-engine) training. Dale requested pursuit even though they couldn’t be over five feet ten nor weigh more than 170 pounds. Dale was five nine but weighed at least 185. “I hope they squeeze me in on pursuit,” he agonized. “I want something fast and maneuverable. If they put me in a bomber school it will make me sick.”

At the end of November, a very disappointed Dale wrote home that he was being sent to twin-engine school. About a third of his class, “little guys who are less than 5 ft. 9 in. and weigh less than 170 lbs.,” were going to Williams Field, Arizona. The other two-thirds, including Dale, were ordered to Roswell, New Mexico. “My only hope now is a P-38,” he said, referring to the large twin-engine, twin-boom fighter plane called the Lightning.

But Dale decided that twin-engine training would probably be worth more in the long run, since flying after the war would mostly be multiple engines, even up to six. “I’m going to keep putting in for pursuit and maybe I’ll end up in a P-38,” he said. “I’d sure like that.”

Advanced Training

The Cessna AT-17 and the Curtiss AT-9 were used for Advanced Training, and ten North American B-25 Mitchell bombers were also sent to the base at Roswell.

Men who had requested medium bombardment were to get twenty hours in them there. Dale had logged forty flying hours, so he did get twenty more in the B-25. He said they were “really built keen,” and cruised about 250 miles per hour.

The Advanced cadets ordered their officer uniforms for graduation. When they arrived, Dale said, “Boy, we’re practically Lieutenants!”

The time had gone faster for him there than at any other base. Dale and another flier had been on a search mission along the Rio Grande for a missing plane. This is why the trainers were usually painted blue and yellow so they’d be easier to spot. They’d stopped at Deming to refuel and have dinner, then buzzed a ranch and some antelope. They didn’t find the missing plane, but Dale said it was the most fun he’d ever had.

Dale sent home three books on flying for his younger brother. And a graduation announcement.

Wings!

Family members were invited to attend the graduation, but it was just too difficult for farmers with livestock to travel that far. It was the custom of a new pilot with a wife or girlfriend to pin wings on her coat, or on his mother’s coat.

Roswell Army Flying School’s Class 43-B graduation was held Saturday morning, February 6, 1943, at 9:00 in the Post Theater. Dale was commissioned a Second Lieutenant, Air Corps, Army of the United States, and he was awarded his silver pilot’s wings. The new lieutenants smoked cigars. Dale spent the rest of the afternoon in his tent. Sick.

Second Lieutenant Dale Wilson got a furlough right after graduation and returned to Iowa, where bestowed his wings on his mother’s coat. After graduation, the new officers were sent to Transition Training bases to learn and practice tactics in whatever plane they would be assigned to fly in combat. Dale was sent to Greenville, SC for B-25 Transition.

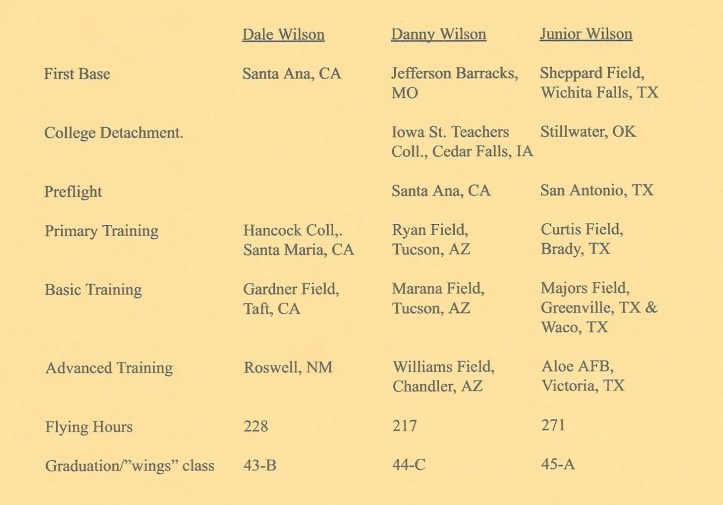

The class was designated by the year and order of graduation. A was the first graduating class of each year.

Before my folks were married, my dad, Warren Neal enlisted about the same time as Dale Wilson. Dad started out at Santa Ana just ahead of Dale. He went to Primary at Thunderbird Field, Glendale, AZ. Basic was at Marana, AZ, and Advanced at Marfa, TX. His parents drove down from Iowa to see him commissioned and get his wings–the same day Dale Wilson got his commission and wings at Roswell.

For more about Dale Wilson, click on his name in the tags below.

I have enjoyed reading this.

Thank you. Working on more today!

[…] https://joynealkidney.com/2018/02/16/dale-earns-his-wings/ […]

[…] Wings! […]

I greatly enjoyed the story of Dale’s flight training. I particularly like how you use specific details to take us through each stage of the training, what it was like, and what emotions Dale felt as he progressed through each stage. Brava!

My dad went through similar training. I couldn’t tell the planes apart (still have to look up the trainers), but enjoyed learning what they looked like compared to how the brothers described them. Thank you, Liz.